Text Message Archiving Strategy Series

Post 1: Why Do Government Agencies Need a Text Message Archiving Strategy?

Government and public-sector employees are increasingly using text messaging to communicate about official business. And those communications, even if conducted on privately owned devices, are public records.

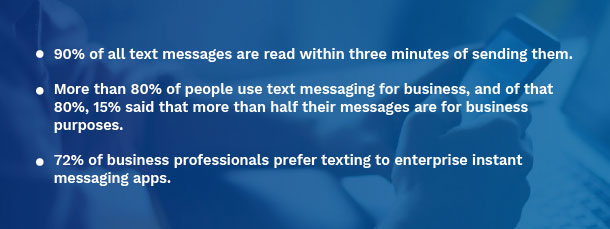

Whether it's used for personal or work, texting has become a pervasive communication channel. People read and respond to text messages immediately, and shifting between personal business and official business has never been so efficient. It's easy to see the uptick looking at three statistics from the OneReach study:

It stands to reason that as the private sector fully leverages this instant, efficient and effective communications channel, the public sector would be following the very same upward trajectory recognizing the value-or the demand-of text communications as well.

As we discussed in last year's 2017 Electronic Communications Survey Report for Public Sector, nearly half of survey respondents identified SMS/text messaging as the most requested channel for conducting agency business, tied with Facebook and Twitter as the most requested.

At the same time, public-sector organizations need to come to grips with the reality that text messages pertaining to government business must be retained and preserved to stay in compliance with open records laws (like the Freedom of Information Act) going forward and reduce risks of litigation centered on content that couldn't be produced.

The Ubiquity of Text Messaging

In 2008 texting was less of an issue. If you did use a mobile device to conduct business, it was a BlackBerry owned by your agency that had tight controls in place governing its use. At that point, public sector IT departments (along with enterprises in general) had firm command over mobile devices.

Meanwhile, smartphone and other mobile devices had not yet reached a tipping point, mostly because they hadn't yet saturated the marketplace. In 2008 the iPhone had only been available for a year and was too expensive for the average consumer and lacked the level of security any enterprise, let alone a public agency required. Also, the first commercially available Android device wasn't even released until later that year. Finally, texting was tedious on typical cell phones of the era (remember having to press the "1" button three times to type a "C?"), so it hadn't yet emerged as a viable, let alone, preferred method of communication.

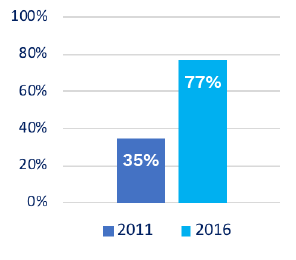

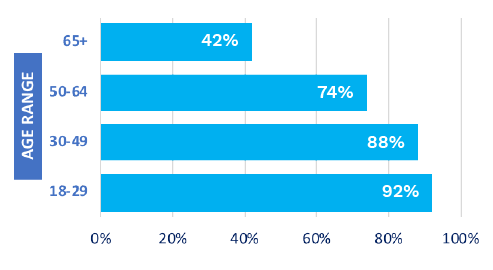

Within a few years, that paradigm was upended. Smartphone adoption rose dramatically, more than doubling in the overall U.S. population from 35% in 2011 to 77% in 2016, the Pew Research Center reports. Among adults 18-29, that percentage is 92%; adults 30-49 are not far behind at 88%.

% of U.S. adults who say they own a smartphone

Given the ubiquity of smartphones in our lives, it's a natural progression that text messaging has become a common form of communication. Think about how our work lives have changed with the advent of the smartphone. If you're an older Millennial, you may remember having to log onto your company PC to schedule, update or cancel a meeting. If you're a Baby Boomer, you may remember having to use the phone to do the same.

And consider the flexibility smartphones provide us today. After a meeting, isn't it a relief to quickly communicate feedback or new ideas through a text no matter where you are, rather than having to write up a formal email at the office hours or even days later?

Yes, Text Messages Are Public Records

Despite the indisputable growth of this communication channel for work, a surprising number of public-sector agencies have not considered text messages to be an electronic public record. Several recent court cases, however, should disabuse anyone of such an outdated notion.

Washington State: In August 2015, the Washington State Supreme Court ruled unanimously that employee text messages sent or received on a private cell phone are public records. The Court overturned the trial judge's ruling that an individual's private cell phone's records were not public records, citing an order from 2010 that ruled the state's Public Records Act (PRA) covered data stored on PCs.

The Court wrote:

If the PRA did not capture records individual employees prepare, own, use, or retain in the course of their jobs, the public would be without information about much of the daily operation of government. Such a result would be an affront to the core policy underpinning the PRA-the public's right to a transparent government [emphasis added]. That policy, itself embodied in the statutory text, guides our interpretation of the PRA.

California: In March 2017, the California Supreme Court, in another unanimous decision, similarly ruled that text messages captured on privately owned mobile devices should be considered public records if the information is related to public business.

As Smarsh General Counsel Bonnie Page wrote last April:

Consistent with other states' rulings, the California Supreme Court ruled that emails and text message communications are not excluded from disclosure under the California Public Records Act when they are on a personal account or device. Rather, the court ruled that it is the content, not the location of a communication, that determines whether an email or text message is a public record. ... [M]any other state and local agencies [have] also assume[d] that privacy law protects communications on employee personal phones or accounts. However, the California Supreme Court specifically held that individual privacy rights are not subservient to public records disclosure.

Meanwhile, Florida views texts as public records in its reference guide for complying with the state's public records laws:

In 2010, the Attorney General's Office advised the Department of State ... that the same rules that apply to e-mail should be considered for electronic communications including Blackberry PINS, SMS communications (text messaging), MMS communications (multimedia content), and instant messaging conducted by government agencies. ... [T]he Department revised the records retention schedule to recognize that retention periods for text messages and other electronic messages or communications "are determined by the content, nature, and purpose of the records, and are set based on their legal, fiscal, administrative, and historical values, regardless of the format in which they reside or the method by which they are transmitted."

These examples are not exceptions. Instead, they are part of a groundswell of legal opinion and laws that view texts and mobile communications as public correspondence, subject to the same laws as other correspondence in the public space. Missouri, has been a recent hotbed for public records activity, is just the latest case proving the inevitability of this fact. Most recently, the Missouri Alliance for Freedom asked the State Attorney General to investigate the State Auditor's failure to produce text messages. This is happening on the heels of reports by the Kansas City Star that Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens and his senior staff were using an app called Confide that automatically deletes text messages after they are exchanged.

These examples are not exceptions. Instead, they are part of a groundswell of legal opinion and laws that view texts and mobile communications as public correspondence, subject to the same laws as other correspondence in the public space. Missouri, has been a recent hotbed for public records activity, is just the latest case proving the inevitability of this fact. Most recently, the Missouri Alliance for Freedom asked the State Attorney General to investigate the State Auditor's failure to produce text messages. This is happening on the heels of reports by the Kansas City Star that Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens and his senior staff were using an app called Confide that automatically deletes text messages after they are exchanged.

The governor has argued that the messages fall under the office's record retention policy as "transitory/administrative" which are not required to be retained. Interest groups like the Missouri Alliance for Freedom and the media (The St. Louis Post-Dispatch called Greitens' actions, "an affront to democracy"), have been vocal critics of the administration's position. As a result of all of this activity, Missouri Sunshine Laws may be amended soon:

- Proposed Missouri House Bill 1817, introduced on January 4, prohibits members and employees of public governmental bodies from using software designed to send encrypted messages that automatically self-destruct to conduct public business.

- In conjunction, Missouri House Speaker Todd Richardson said the Legislature may consider modernizing the state's Sunshine Law, and specifically addressed text messages in his statements.

And for those of you who still have their metaphorical heads in the sand, the Capstone 2019 requirements, which are now only a year away, has expanded its reach from its 2016 requirements (which only included email in its message types) to "all permanent records in an electronic format." In other words, federal agencies will be responsible for managing text messages, along with anything else that falls under the "electronic records" umbrella "for eventual transfer and accessioning by NARA (National Archives and Records Administration) in an electronic format" by December 31, 2019.

Text Message Archiving Solution: The Only Feasible Option

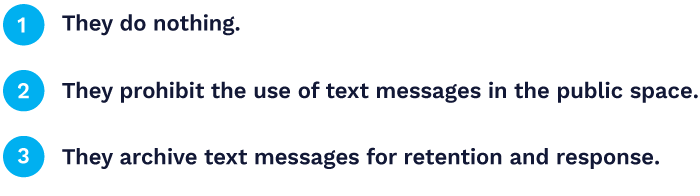

In our previously referenced 2017 Electronic Communications Survey for Public Sector, we found government organizations typically do one of three things to manage any text messages that could be construed as public communications:

The aforementioned judicial and legislative trends prevent you from "doing nothing," unless you want your agency mired in litigation, fines and other costs relating to non-compliance. And a blanket prohibition of texting, whether on agency-owned devices or employees' own devices, is next to impossible because, texting is the fastest, most immediate and oftentimes most effective channel of communications available. What government agency has the budget, let alone the inclination, to make sure such a prohibition policy is followed?

Really, the only sensible option is to develop a text message archiving strategy that gives your agency the capability to store all texts related to agency business in a way that makes them accessible during any FOIA or other document review request that comes your way.

Acknowledging the need of a text message archiving strategy is one thing. Figuring out the particulars of doing and the challenges you face in this undertaking is something else. We will discuss these challenges in our next post.

In the meantime: If you're curious about the progress of this issue in your state, check out Smarsh's handy interactive guide FOIA Laws - Interactive Map of Sunshine Laws by State as a starting point.